|

The Self-Organisation of

Society- Part II 2.1.2 The Synchronous

Description of Society 2.1.3 The Diachronic Description of Society 2.2. Society as the Unity of Different

Qualitative Systems 2.1.2 The Synchronous Description of

Society

There is a difference between

employing words for a curtate description of empirically given phenomena and

employing words as a sort of “glasses” for viewing the world (categories). The notion of “society” first of

all means thinking about human beings and imagining “all human beings together”

as society. This is the empirical concept of society. Unity here is considered

as a unity of many human beings and can be described in two different ways: on

the one hand in its systematic structure (synchronous) and on the other hand as

temporal process (diachronic). Concerning the philosophical concept of

dialectic we employ, the first approach refers to the dialectical logic

(logical relationships of categories) and the second to the historical logic

(temporal evolution) – here still within the logic of essence[i].

We first deal with the synchronous description of society. Sociological theories can be categorised

by the way they relate structures and actors (see Fuchs/Hofkirchner/Klauninger

2002). Individualistic and subjectivistic theories consider the human being as

an atom of society and society as the pure agglomeration of individual existences.

Structuralistic and functionalistic theories stress the influence and

constraints of societal structures on the individual and actions. Dualistic

sociological theories conceive the relationship of actors and structures as

independent, arguing that actors are psychological systems that don’t belong to

societal systems. Finally, dialectical approaches try to avoid one-sided

solutions of this foundational problem of sociology and conceive the

relationship of actors and structures as a mutual one. Functionalist and structuralistic

positions are unable to see human beings as reasoning, knowledgeable agents

with practical consciousness and argue that society and institutions as

subjects have needs and fulfil certain functions. This sometimes results in

views of a subjectless history which is driven by forces outside the actors’

existence that they are wholly unaware of. The reproduction of society is seen

as something happening with mechanical inevitability through processes of which

societal actors are ignorant. Functionalism and structuralism both express a

naturalistic and objectivistic standpoint and emphasise the pre-eminence of the

societal whole over its individual, human parts. Mechanistic forms of

stucturalism reduce history to a process without a subject and historical

agents to the role of supports of the structure and unconscious bearers of

objective structures (Althusser). In individualistic social

theories structural concepts and constraints are rather unimportant and quite

frequently sociality is reduced to individuality. There is a belief in fully

autonomous consciousness without inertia. E.g. methodological individualists

such as von Mises, Schumpeter and von Hayek claim that societal categories can

be reduced to descriptions of the individual. “If interpretative sociologies

are founded, as it were, upon an imperialism of the subject, functionalism and

structuralism propose an imperialism of the social object“ (Giddens 1984: 2). In Hegelian terms, individualism

reduces society to individual being-in-itself or abstract, pure-being, whereas

structuralism and functionalism consider the role of the human being in society

merely as being-for-another and determinate-being. Only dialectical approaches

to society consider the importance of both aspects, unity as being-in-and-for-itself.

Already Hegel criticised atomistic philosophies (Hegel 1830I: §§ 97, 98) by

saying that they fix the One as One, the Absolute is formulated as

Being-for-self, as One, and many ones. They don’t see that the One and the Many

are dialectically connected: the One is being-for-itself and related to itself,

but this relationship only exist in relationship to others (being-for-another)

and hence it is one of the Many and repulses itself. But the Many are one the

same as another: each is One, or even one of the Many; they are consequently

one and the same. As those to which the One is related in its act of repulsion

are ones, it is in them thrown into relation with itself and hence repulsion

also means attraction. Also Marx criticised the reductionism

of individualism in his critique of Max Stirner (Marx/Engels 1846: 101-438) and

put against this the notion of the individual that is estranged in capitalism

and that can only become a well-rounded individual in communism. Stirner says

that the individual can only be free if it gets rid of dominating forces such

as religion, state, and even society and humankind. He argued in favour of a

“union of egoists” and stressed the superiority of the individual and the

uniqueness of the ego. Societal forces would be despotic, they would limit and

subordinate the ego of the individual. Marx interposes that: 1.

individualism doesn’t see the necessarily societal and material interdependence

of individuals and doesn’t grasp their process of development because it limits

itself to advise them that they should proceed from themselves. “Individuals have always and in all

circumstances “proceeded from themselves”, but since they were not unique

in the sense of not needing any connections with one another, and since their needs,

consequently their nature, and the method of satisfying their needs, connected

them with one another (relations between the sexes, exchange, division of

labour), they had to enter into relations with one another“ (Marx/Engels

1846: 423). 2. Individualism wouldn’t

adequately reflect the real conflicts in the world and due to an idealistic

inversion of the world it would replace political praxis by moralism. Stirner

wants do away with the “private individual” for the sake of the “general”, selfless

man, but consciousness is separated from the individual and its existence in

the real, material world. “It depends not on consciousness, but on being;

not on thought, but on life; it depends on the individual’s empirical

development and manifestation of life, which in turn depends on the conditions

obtaining in the world. If the circumstances in which the individual lives

allow him only the [one]-sided development of one quality at the expense of all

the rest, [If] they give him the material and time to develop only that one

quality, then this individual achieves only a one-sided, crippled development.

No moral preaching avails here“ (Marx/Engels 1846: 245f). In medieval thinking individual

meant inseparability and identity, it was a concept that denoted the

relationship of a private human being to God (mediated by the church). An

individual was defined as a fixed member of a certain group, as inseparable

from its social role. The possibility of becoming something else was very

limited in medieval times. The term individual was connected to the religious

idea of the unity and indivisibility of the Trinity (God, Jesus, Holy Ghost).

Until the 18th century the term individual was rarely used without

explicit relation to the group of which it was the ultimate indivisible

division. With the rise of capitalism mobility increased, at least some men

could change their status. The understanding of the term individual changed and

the individual was considered as being separable from its social role. With the

movement against feudalism and traditional religion there was a stress on a

man’s personal existence over and above society. Individualism has had its rise

with the emergence of modern, i.e. capitalist society and is related to ideas

that have been developed during the course of the enlightenment such as a free

will as well as rationally and responsible acting subjects. The enlightenment

formed an integral element of the process of establishing modern society. The

concept of the modern individual is also one that has been made possible by

questioning religious eschatologies of an unalterable and God-given fate of

humankind. The rise of this modern notion of the individual has also been

interrelated with the rise of the idea of “free” entrepreneurship in market society.

Freedom has been conceived in this sense as an important quality and essence of

the modern individual. The idea of the modern individual can be seen as a

logical consequence of the liberal-capitalist economy. According to this

concept, morally responsible and autonomous personalities can develop on the

basis of economical and political freedom that is guaranteed by modern society

and trade is considered in a model which postulates separate individuals who

decide, at some starting point, to enter economic relationships and produces a

collective result due to their egoistic interests (theorem of the invisible

hand). It also stresses that society guarantees individuality by removing obstacles

to individual freedom and to rational and reasonable actions. In the ideology

of individualism, individuality is clearly identified with following

self-interest economically. Egoism and selfishness are often fetishised by

assuming that they are natural characteristics of all individuals and that they

emerge from rational and autonomous thinking. But it can also be argued that

our modern society is not reasonable because it does not guarantee happiness

and satisfaction of all human beings, in fact these categories are only

achievable for a small privileged elite. Nowadays individuals are not

only seen as owners of a free will, it is also generally assumed that this free

will can be applied in order to gain ownership of material resources and

capital which make it possible to realise individual freedom. So freedom is seen

as something that can be gained individually by striving towards individual

control of material resources. This shows that the concept of the modern

individual is unseparably connected with the idea of private property. The idea

of the individual as an owner has dominated the philosophical tradition from

Hobbes to Hegel and still dominates philosophical ideas about the essence of

mankind. But this concept could never be applied to all humans that are part of

society because the majority of the world population still does not possess all

these idealistically constructed aspects of freedom and autonomy, this majority

is rather confronted with alienation and the disciplinary mechanisms of

compulsions, coercion and domination. Hence the modern idea of the individual

can be seen as an ideology that helps to legitimate modern society. The idea of

already existing autonomous individuals may be a nice ideal, but nonetheless it

can today be seen as nothing more than imagination and self-deception. Besides individualism and

structuralism, there is also dualism. In sociology, the main representative of

the sciences of complexity is Niklas Luhmann. Luhmann argues that action-based

conceptions of society are reductionistic because they reduce societal order to

rational human beings and that they can’t adequately explain the increasing

complexity of modern society as well as emergent properties of societal systems

(Luhmann 1984: 347). Luhmann wrongly infers from this that the explanation of

societal relationships should neglect acting subjects. This results in a

dualistic theory that due to the neglect of human subjects itself can’t

adequately explain the bottom-up-emergence of societal structures and the

top-down-emergence of actions and behaviour. Luhmann’s theory has been

criticised as deterministic one because he doesn’t adequately reflect the wide

contingency of societal systems that is due to the fact that action involves

the realisation of one of several possibilities in a specific societal

situation. Luhmann argues that self-reproduction is a necessity of a societal

system that is not based on human actions (Luhmann 1984: 395, 655), conceives

society in functional terms, applies Maturana’s and Varela’s

autopoiesis-concept sociologically and sees society as a self-referential

system with communications as its elements. He argues that individuals are

(re)produced biologically, not permanently by the societal systems. If one

wants to consider a societal system as autopoietic or self-referential, the

permanent (re)production of the elements by the system is a necessary

condition. Hence Luhmann says that not individuals, but communications are the

elements of a societal system. A communication results in a further

communication, by the permanent (re)production of communications a societal

system can maintain and reproduce itself. Luhmann can’t explain how one

communication can exactly produce other communications without individuals

being part of the system. An autopoietic conception of society must show

consistently that and how society produces its elements itself. Luhmann does

not show how communications are produced, he only mentions that communications result in

further communications. He can explain that society is self-referential in the

sense that one communication is linked to other ones, but he can’t adequately

explain that it is self-producing or autopoietic. Luhmann’s abandonment of the

human subject in society results in functionalist descriptions that have no

room for critical considerations of how society could or should be in. He says

himself that he does not have an agenda of a societal problems-approach and it

has been criticised that he wants to deny critical and oppositional thinking

their legitimacy. Things only have to function, Luhmann sees the task of sociology

in locating disfunctionalities and eliminating them. This theory is only

critical in the sense that it is critical against all oppositional movements

and of opposition. Warnke (1977) argues that with relativism and perspectivism

Luhmann and other system theorists try to eliminate the philosophical

categories totality, concrete-universal and essence and replace the

dialectical-materialist demand for concretness by an abstract philosophical

body. Contrary to pausing at the abstract thing-in-itself or the abstract

being-for-another dialectical philosophy would be in a mediation of both in the

being-in-and-for-itself which means concretisation. Luhmann’s concept of a

system would see a whole as something complete and finished, whereas the

dialectical concept of totality would consider a whole as developing and

becoming as well as an endless process of parts and wholes sublating their

difference by each moment passing over into the other and again composing their

difference through unity. A consistent alternative that

bridges the shortcomings of individualism, structuralism and dualism is a

dialectical theory of society. By saying that societal self-organisation means

the self-reproduction of a societal system, one must specify what is being

reproduced. Applying the idea of self-(re)production to society means that one

must explain how society produces its elements permanently. By saying that the

elements are communications and not individuals as Luhmann does, one can’t

explain self-reproduction consistently because not communications, but human

beings produce communications. One major problem of applying autopoiesis to

society is that one cannot consider the individuals as components of a societal

system if the latter is autopoietic. Applying autopoiesis nonetheless to

society will result in subject-less theories such as the one of Luhmann that

can not explain how individuals (re)produce societal structures and how their

sociality is (re)produced by these structures. Another alternative would be to

argue that society can reproduce itself by the biological reproduction of the

individuals, but doing so will result in the neglect of the differentia

specifica of society. Neither assuming society is a

self-referential communication system, nor describing society in terms of

biological reproduction provides us with an adequate idea of how the

self-reproduction of society takes place. Society can only be explained

consistently as self-reproducing if one argues that man is a societal being and

has central importance in the reproduction-process. Society reproduces man as a

societal being and man produces society by socially co-ordinating human

actions. Man is creator and created result of society, society and humans

produce each other mutually. Such a conception of societal self-organisation acknowledges

the importance of human actors in societal systems. Saying that man is creator

and created result of society corresponds to Giddens’ formulation that in and

through their activities agents reproduce the conditions that make these

activities possible (Giddens 1984: 2). The individual is a societal,

self-conscious, creative, reflective, cultural, symbols- and language-using,

active natural, labouring, producing, objective, corporeal,

living, real, sensuous, anticipating, visionary, imaginative, expecting,

designing, co-operative, wishful, hopeful being that makes its own history and

can strive towards freedom and autonomy (see Fuchs 2002f). In the societal production of

their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are partly

dependent and partly independent of their will. By societal actions, societal

structures are constituted and differentiated. The structure of society or a

societal system is the totality of behaviours. A specific structure involves a

certain regularity of societal relationships which make use of artefacts.

Societal structures don’t exist externally to, but only in and through agency.

In societal formations such as capitalism societal structures are alienated

from the human being and the human being estranges itself from the societal

structures because certain groups determine the constitution and development

process of these structures and exploit others for facilitating these

processes. Alienated societal structures still exist only in and through

agency, but some groups have privileged access to and control of these structures,

whereas it is much harder for others to influence them according to their own

needs and interests. Societal structures in alienated societies are an object and

realm of societal struggle. By societal interaction, new

qualities and structures can emerge that cannot be reduced to the individual

level. This is a process of bottom-up emergence that is called agency.

Emergence in this context means the appearance of at least one new systemic

quality that can not be reduced to the elements of the systems. So this quality

is irreducible and it is also to a certain extent unpredictable, i.e. time,

form and result of the process of emergence cannot be fully forecasted by

taking a look at the elements and their interactions. Societal structures also

influence individual actions and thinking. They constrain and enable actions.

This is a process of top-down emergence where new individual and group

properties can emerge. The whole cycle is the basic process of systemic

societal self-organisation that can also be called re-creation because by

permanent processes of agency and constraining/enabling a societal system can

maintain and reproduce itself (see fig. 1). It again and again creates its own

unity and maintains itself. Societal structures enable and constrain societal

actions as well as individuality and are a result of societal actions (which

are a correlation of mutual individuality that results in sociality).

structures

constraining and enabling agency Fig. 1.: The

self-organisation/re-creation of societal systems Terming the self-organisation of

society re-creation acknowledges as outlined by Giddens the importance of the

human being as a reasonable and knowledgeable actor in sociology. Giddens

himself has stressed that the duality of structure has to do with re-creation:

“Human social activities, like some self-reproducing items in nature, are

recursive. That is to say, they are not brought into being by social actors but

continually recreated

by them via the very means whereby they express themselves as actors“ (Giddens

1984: 2). Saying that society is a re-creative or self-organising system the

way we do corresponds to Giddens’ notion of the duality of structure[ii]

because the structural properties of societal systems are both medium and

outcome of the practices they recursively organise and both enable and

constrain actions. Societal systems and their reproduction involve conscious,

creative, intentional, planned activities as well as unconscious, unintentional

and unplanned consequences of activities. Both together are aspects, conditions

as well as outcomes of the overall re-creation/self-reproduction of societal

systems. The mutual relationship of

actions and structures is mediated by the habitus, a category that describes

the totality of behaviour and thoughts of a societal group (for the importance

of Pierre Bourdieu’s conceptions such as the habitus for a theory of societal

self-organisation see Fuchs 2002b). The habitus is neither a pure objective,

nor a pure subjective structure, it means invention (Bourdieu 1977: 95, 1990b: 55).

In society, creativity and invention always have to do with relative chance and

incomplete determinism. Societal practices, interactions and relationships are

very complex. The complex group behaviour of human beings is another reason why

there is a degree of uncertainty of human behaviour (Bourdieu 1977: 9, 1990a:

8). Habitus both

enables the creativity of actors and constrains ways of acting. The habitus

gives orientations and limits (Bourdieu 1977: 95), it neither results in

unpredictable novelty nor in a simple mechanical reproduction of initial

conditionings (ibid.: 95). The habitus provides conditioned and conditional

freedom (ibid.: 95), i.e. it is a condition for freedom, but it also conditions

and limits full freedom of action. This is equal to saying that structures are

medium and outcome of societal actions. Very much like Giddens, Pierre Bourdieu

suggests a mutual relationship of structures and actions as the core feature of

societal systems. The habitus is a property “for which and through which there

is a social world” (Bourdieu 1990b: 140). This formulation is similar to saying

that habitus is medium and outcome of the societal world. The habitus has to do

with societal practices, it not only constrains practices, it is also a result

of the creative relationships of human beings. This means that the habitus is

both opus operatum (result of practices) and modus operandi (mode of practices)

(Bourdieu 1977: 18, 72ff; 1990b: 52). In the Liberal-individualistic

tradition (e.g. Hobbes, Locke) the individual was postulated as an axiom and

society derived from it. In the collectivist tradition (e.g. Rousseau, Hegel)

one starts from society or the State and derives the individual from it. The

founder of Cultural Materialism Raymond Williams (1961) says that there must be

mediating terms between individual and society such as relationships, class,

association or community in order to avoid reductionism. Erich Fromm suggested

the mediating term ‘social character’, in anthropology one speaks of a ‘pattern

of culture’. Bourdieu’s concept of the habitus is also a mediating category,

Williams already pointed out implicitly the necessity of the notion of the

habitus at the beginning of the 1960ies. Williams wants to avoid both an

absolute totalisation of society and the individual. He considers the

individual as a societal being and each individual as unique. “The conscious

differences between individuals arise in the social process. To begin with,

individuals have varying innate potentialities, and thus receive social

influence in varying ways. Further, even if there is a common ‘social

character’ or ‘culture pattern’, each individual’s social history, his actual

network of relationships, is in fact unique” (Williams 1961: 74). The

individual is unique for Williams due to a particular heredity expressed in a

particular history. Society is not a uniform object, individuals enter various

groups and hence Williams says that due to the fact that the individual

encounters tensions, conflict as well as co-operation in these relationships

and as a result of the interactions in groups and between them, new directions

emerge in society. Williams distinguishes several types of individuals: members,

subjects, servants, rebels/revolutionaries, reformers, critics, exiles, vagrants

and self-exiles/internal émigre[iii].

We would need such descriptions in order to get past the impasse of the simple

distinction between conformity and non-conformity. For Williams these forms are

forms of active organisation (action, interaction), he considers the

relationship of the individual and society as a complicated embodiment of a

wide area of real relationships where certain forms may be more influencing

than others. Society would not just act upon the individual, but also many

unique individuals through a process of communication create the organisation

by which they will continue to be shaped. The uniqueness of the individual is

“creative as well as created: new forms can flow from this particular form, and

extend in the whole organization, which is in any case being constantly renewed

and changed as unique individuals inherit and continue it” (Williams 1961: 82).

The relationships individuals enter are creative, social change and emergent

properties result from it, and these resultant patterns create, i.e. enable and

constrains, the individual’s history of thinking and actions. Williams’

concepts corresponds to (and in fact anticipated) the reflexive categories of

Giddens and Bourdieu. Saying that the uniqueness of the individual is creative

and created complies with Giddens’ formulation that in and through their

activities agents reproduce the conditions that make these activities possible

as well as to Bourdieu’s formulation that habitus provides conditioned and

conditional freedom and is a property for which and through which there is a

social world. “If man is essentially a learning, creating and communicating

being, the only social organization adequate to his nature is a participatory

democracy, in which all of us, as unique individuals, learn, communicate and

control. Any lesser, restrictive system is simply wasteful of our true

resources; in wasting individuals, by shutting them out from effective participation,

it is damaging our true common process” (Williams 1961: 83). In modern sociology, Pierre

Bourdieu and Anthony Giddens have devoted their work to bridging the

traditional, strict oppositions between subjectivity/objectivity,

society/individual, structures/action and consciousness/unconsciousness

dialectically. They both want to solve the problem of relating societal

structures and actions dialectically. Bourdieu has introduced the dialectical

concept of the habitus that mediates between objective structures and subjective,

practical aspects of existence. The habitus secures conditioned and conditional

freedom, it is a structured and structuring structure that mediates the

dialectical relationship of the individual and society. For Bourdieu, in the

societal world we find dialectical relationships of objective structures and

the cognitive/motivational structures, of objectification and embodiment, of

incorporation of externalities and externalisation of internalities, of

diversity and homogeneity, of society and the individual and of chance and

necessity. Bourdieu’s suggestion that the habitus is a property for which and

through which there is a social world means that habitus is medium and outcome

of the societal world and that societal structures can only exist in and

through practices. Such formulations very much remind us of Giddens’ main hypothesis

that the structural properties of

societal systems are both the medium and the outcome of the practices that

constitute those systems. Although

Bourdieu’s theory might be considered a more “structuralistic” conception than

Giddens’, the similarities concerning aims and certain theoretical contents are

very striking and aspects from both theories can enhance a theory of societal

self-organisation (see Fuchs 2002a, b). The notion of the re-creation of

society suggest a dialectical relationship of structures and actors. Saying

this, one should clarify why exactly this is a dialectical relationship. Georg

Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel has outlined that the purpose of dialectics is “to

study things in their own being and movement and thus to demonstrate the

finitude of the partial categories of understanding” (Hegel 1830I: Note to

§81). The dialectical method “serves to show that every abstract proposition of

understanding, taken precisely as it is given, naturally veers round its

opposite” (ibid.). The negative constitutes the genuine dialectical moment

(Hegel 1830I: §68), “opposites [...] contain contradiction in so far as they are,

in the same respect, negatively related to one another or sublate each other and are indifferent to

one another“ (ibid.: §960) Opposites, therefore, contain contradiction in so

far as they are, in the same respect, negatively related to one another or sublate each

other and are indifferent to one another. But the

negative is just as much positive (§62). The result of Dialectic is positive,

it has a definite content as the negation of certain specific propositions

which are contained in the result (§82). An

entity as pure being is an identity, an abstract empty being. Being is

dialectically opposed to Nothing, the unity of the two is Becoming. In

Becoming, Being and Nothing are sublated into a unity. This unity as result is

Determinate Being which can be characterised by quality and reality. Quality is

Being-for-another because in determinate being there is an element of negation involved

that is at first wrapped up and only comes to the front in Being-for-self.

Something is only what it is in its relationship to another, but by the

negation of the negation this something incorporates the other into itself. The

dialectical movement involves two moments that negate each other, a somewhat

and an another. As a result of the negation of the negation, “Something becomes

an other; this other is itself somewhat; therefore it likewise becomes an

other, and so on ad infinitum” (§93). Being-for-self or the negation of the negation

means that somewhat becomes an other, but this again is a new somewhat that is

opposed to an other and as a synthesis results again in an other and therefore

it follows that something in its passage into other only joins with itself, it

is self-related

(§95). In becoming there are two moments (Hegel 1812: §176-179): coming-to-be

and ceasing-to-be: by sublation, i.e. negation of the negation, being passes

over into nothing, it ceases to be, but something new shows up, is coming to

be. What is sublated (aufgehoben) is on the one hand ceases to be and is put to

an end, but on the other hand it is preserved and maintained (ibid.: §185). In

society, structures and actors are two opposing moments: a structure is a

somewhat opposed to an other, i.e. actors; and an actor is also a somewhat

opposed to an other, i.e. structures. The becoming[iv] of society is

its permanent dialectical movement, the re-creation or self-reproduction of

society. The Being-for-self or negation of the negation in society means that

something societal becomes an other societal which is again a societal somewhat

and it likewise becomes an other societal, and so an ad infinitum. Something

societal refers to aspects of a societal system such as structures or actions,

in the dialectical movement these two societal moments in their passage become

an other societal moment and therefore join with themselves, they are

self-related. The permanent collapse and fusion of the relationship of

structures and actors results in new, emergent properties or qualities of

society that can’t be reduced to the underlying moments. In the

re-creation-process of society, there is coming-to-be of new structural and

individual properties and ceasing-to-be of certain old properties. “Becoming is

an unstable unrest which settles into a stable result” (Hegel 1812: §180). Such

stable results are the emergent properties of society. In

respect to Hegel, the term societal self-organisation also gains

meaning in the sense that by the dialectical process where structures are

medium and outcome of societal actions a societal somewhat is self-related or

self-referential in the sense of joining with itself or producing itself. By

dialectical movement, societal categories opposing each other (structures and

actions) produce new societal categories. A societal something is opposed to an

societal other and by sublation they both fuse into a unity with emergent

societal properties. This unity is again a societal somewhat opposed to a

societal other etc. By coming-to-be and ceasing-to-be of societal entities, new

societal entities are produced in the dialectical societal process. For

Marx the individual is of great importance in his social analysis, not as an

isolated atom, but as a societal being that is the constitutive part of

qualitative moments of society and has a concrete and historical existence. “The first premise of all human history is,

of course, the existence of living human individuals“ (Marx/Engels 1846: 20).

He considers the individual in its abstract being-for-self, its connectedness

to others and its estrangement in modern, capitalist society. The individual as

a societal, producing being (“individuals co-operating in

definite kinds of labour“) results in phenomena such as modes of life, increase

of population (family), forms of intercourse (Verkehrsformen), separation of

town and country, forms of politics (nation state), division of labour, forms

of ownership (tribal ownership, ancient communal and State ownership, feudal or

estate property (feudal landed property, corporative movable property, capital

invested in manufacture), capital as pure private property), production of

ideas, notions and consciousness. For Marx, a certain mode of production is

combined with a certain mode of co-operation (ibid.: 30) and the history of

humanity is closely connected to the history of the economy. Opposing the

atomism of Max Stirner and Bruno Bauer, Marx writes that the “individuals

certainly make one another, physically and mentally, but do not make themselves“

(ibid.: 37). In the German Ideology (Marx/Engels

1846), Marx

speaks of societal relationships as forms of intercourse, whereas he later

replaced this term by the one of relationships of production. He says that with

the development of the productive forces, the form of intercourse becomes a

fetter and in place of it a new one is put which corresponds to the more

developed productive forces and hence “to the advanced mode of the

self-activity of individuals” – a form which in its turn becomes a fetter and

is then replaced by another etc. The history of the forms of intercourse would

be the history of the productive forces and hence the history of the

development of the forces of the individuals themselves (ibid.: 72). Marx considers man in the Economic and

Philosophical Manuscripts (Marx 1844) as an universal, objective

species-being that produces and objective world and reproduces nature and his

species according to his purposes. Human beings are societal beings, they enter

societal relationships which are mutually dependent actions that make sense for

the acting subjects. Individual being is only possible as societal being,

societal being (the species-life of man) is only possible as a relationship of

individual existences. This dialectic of individual and societal being (which

roughly corresponds to the one of individual and societal existence or of

actors and structures) was already pointed out by Marx: “The individual is the

social

being. His manifestations of life – even if they may not appear in

the direct form of communal manifestations of life carried out in association

with others – are therefore an expression and confirmation of social life.

Man's individual and species-life are not different, however much –

and this is inevitable – the mode of existence of the individual is a more particular or

more general mode of the life of the species, or the life of the species is a

more particular

or more general individual life“ (Marx 1844: 538f). Marx said one

must avoid postulating society again as an abstraction vis-à-vis the individual as

e.g. today individual/society-dualism does. “Man, much as he may therefore be a

particular

individual (and it is precisely his particularity which makes him an

individual, and a real individual social being), is just as much

the totality

– the ideal totality – the subjective existence of imagined and experienced

society for itself; just as he exists also in the real world both as awareness

and real enjoyment of social existence, and as a totality of human manifestation

of life“ (ibid.). Saying that man is creator and created result of society as

well as that in and through their activities agents reproduce the conditions

that make these activities possible, corresponds to Marx’ formulation that “the

social character is the general character of the whole movement: just as

society itself produces man as man, so is society produced by him“ (ibid.:

537). Up until now we have only considered the systematic aspect of the

self-reproduction of society as a whole towards its parts. It is also an

important question how these systematic relationships develop temporally. We

will have different results depending on which approach we choose: one that is

based on concepts of self-organisation and systems theory, or one that is based

on a historical-concrete analysis of societal forms. 2.1.3 The

Diachronic Description of Society

Society is not a static state,

but a permanently self-maintaining and self-renewing process. In a first

approximation, a living organism can be used as an analogy for this process.

The living is characterised by self-maintenance: “We recognise that a

dispensing order has the power to maintain itself and to produce ordered

processes”[v]

(Schrödinger 1987: 74). The individuals however are in this concept only indifferent

against each other, the parts are not defined as inner qualitative difference

to each other (Hegel 1830II/1986: 373, § 343 corollary). Such a neglect of the

individual distinctiveness as subjects of society is connected to the point of

view which tries to primarily describe the identical self-reproduction of

society. Such descriptions can mainly be found in old systems theory (1st

order cybernetics) which are based on equilibrium theories (e.g. the social

systems theory of Talcott Parsons). The concept of autopoiesis, which not

accidentally stems from biology, is transferred by one of its main proponents,

Humberto Maturana, to society, whereas Francisco Varela opposes such an application.

Also the newer concepts of self-organisation stress first the emergence of

systematic wholes from interactions of their parts. Self-organisation as

“irreversible process which results from the co-operative interaction of

subsystems in complex structures of the whole system”[vi]

(Ebeling/Feistel 1986) or as synergetics where a “cyclical causality” (Haken)

between whole and parts is assumed, correspond to this idea. However the

concepts of self-organisation have new potentialities: they refer to

qualitative changes. As “new systems theory” they also refer to the unpredictability

of structural breaks. Maybe not accidentally this thinking has become modern at

the time when the limits of steering in the manner of the “welfare state” first

showed up (see Müller 1992: 343). These concepts which are based on

non-equilibrium, non-linearity and the existence of fluctuations, show at least

the inappropriateness of the old equilibrium models and are meanwhile also used

in economics and management theory. However, most of the existing concepts of

economic self-organisation legitimise neo-liberal politics by arguing that

human beings can’t at all intervene into the capitalist economy in order to

solve social problems and that hence market-based regulation will do best (see

Fuchs 2002g). That this is not the case is clear due to the worsening of the

global problems in the last two decades of neo-liberal politics in the world

system. A number of authors have tried

to conceive sociological models in analogy to Ilya Prigogine’s abstract

principle of order through fluctuation. They see society as a system where not

equilibrium and stability is the normal state, but non-equilibrium and

instability. Modern society is described as process-like and evolving through

phases of crisis and instability. Ervin Laszlo (1987) argues that

Prigogine’s principle is a general one that applies for the evolution of all

complex systems, also for society. According to this hypothesis systems do not

remain stabile, if certain parameters are crossed, instabilities emerge. These

are phases of transition where the system shows high entropy and high degrees

of indetermination, chance and chaos. Evolution does not take place

continuously, but in sudden, discontinuous leaps. After a phase of stability a

system enters a phase of instability, fluctuations intensify and spread out. In

this chaotic state, the development of the system is not determined, it is only

determined that one of several possible alternatives will be realised. Such

points in evolution are called catastrophic bifurcation (Laszlo 1987, Schlemm

1999, Fuchs 2002c, d). In a very abstact form we can say: It is determined that

this evolutionary process will sooner or later result in a large societal

crisis, but it is not fully determined which antagonisms will cause the crisis

and how the result of the crisis will look like. There can be no certainty, the

sciences and hence also the social sciences are confronted with an end of

certainties (Wallerstein 1997). There could e.g. be the emergence of a new mode

of development, the ultimate breakdown of society due to destructive forces or

the emergence of a new formation of society caused by social agency of

intervening subjects. If a certain threshold in the development of concretely

existing antagonisms is crossed, a new, not pre-determined quality will emerge.

This is what Hegel has discussed as the measure or the turn from quantity into

quality (Hegel 1830I: §§107f). Arguing only abstractly doesn’t

take into account the different qualities of societal formations[vii].

In one or the other manner the first humans organised themselves and this

organisation dissolved, somehow large city states, the Greek republic, Asiatic

nomads, capitalism, actually existing “socialism” organised themselves. We need

also more concrete analyses which are not only abstract-general, but also don’t

simply list the sum of all observations and singular phenomena. 2.2. Society as the

Unity of Different Qualitative Systems

For such an approach

dialectical-speculative thinking is needed[viii].

Whereas in usual thinking (within the logic of essence) a starting point is

considered as being already given/posited and further implications are deduced,

in dialectical-speculative thinking (within the logic of notion) the posited

(das Gesetzte) must be given grounds for and hence all thinking must be integrated

into a context of justification and mediation. We distinguish an abstract

generality (“humanity”) from a concrete generality[ix]

where we are referring to concrete societal formations. On such a concrete

level, one can qualitatively describe the mediations which determine the

development of the societal formation in question. We want to outline this

shortly for the concrete-historical societal formation of capitalism: First we have to distinguish

different societal spheres, such as production, consumption, distribution,

politics, culture, etc. In society all spheres are mediated – in order to know

later what is concretely mediated with each other, the single moments must also

be analysed separately. We here concentrate on the capitalist economy. Like in

all societal formations, goods are produced in capitalism that satisfy human

needs. The specific ways this is done distinguish different societal formation.

In capitalism the production process is based on the fact that single economic

actors produce goods which are sold on the market after their production in

order to achieve a profit that allows re-investment, more production, more

selling, again more profit etc. Marx called this process the accumulation of

(money and commodity) capital. Capitalist production doesn’t satisfy immediate

needs (as was e.g. the case in the production of the medieval craftsman), but

each capitalist is in need of the so-called “anonymous market” for the

socialisation of the products. That the single capitalist enterprise produces

in an isolated way, is of course not something biologically given, but a

societal relationship. Marx is speaking of private labour that produces

commodities. Another foundation of capitalism has been the detachment of the

means of production from the workers. Marx is speaking of “double free

wage-labour”, the workers don’t own the means of production and the produced

goods and they are forced to sell their labour power (Marx 1867: 181-183). Wage

labour and the industrial division of labour (which has been enabled by machine

technologies, Marx speaks of machine-systems, large industry or the

co-operation of many similar machines that are powered by a motor mechanism

such as the steam engine, see Marx 1867: chapter 13) are necessary conditions

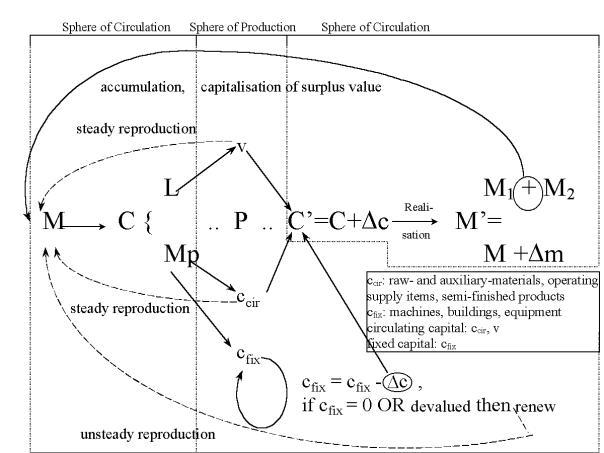

for the full development of capital accumulation. On this foundation a functional circle takes place (according to Fuchs

2000): The capitalist buys with his money (M) the commodities (C) labour power

(L) and means of production (Mp) (these two commodity types are separated – in

another societal formation without the same base the cycle of production takes

place in another way). The means of production are considered in their value

form as constant capital (c) and can be subdivided into circulating constant

capital (the value of the utilised raw materials, auxiliary materials,

operating supply items and semi-finished products) and fixed constant capital

(the value of the utilised machines, buildings and equipment) (Marx 1885:

chapter 8). The value of the employed labour power is termed variable capital

(v). Constant capital is transfused to the product, but it doesn’t create new

value. Only living labour increases value – labour produces more value than it

needs for its own reproduction. In production due to the effects of living

labour onto the object of labour surplus value (s) is produced. The value of a

produced commodity C’ = c + v + m, this value is larger than the value of the

invested capital (C = c + v). The difference of C’ and C (Dw) can exist due to

the production of surplus value and is itself surplus value. Surplus value is

transformed into profit (surplus value is “realised”) and value into money

capital by selling the produced commodities on the market. It is not sure if

all produced commodities can be sold, hence not all surplus value is

necessarily transformed into profit. But normally after the whole process there

is more money capital than has been invested into production, and such “surplus

value generating money” is termed “capital” and is partly re-invested into new

production (accumulation).

Fig. 1.: The economic

self-organisation of capital: The expanded reproduction cycle of capital

Whereas in all societies humans

produce, the way they do this is typically different in different societal

formations. It’s a false inference to generalise the form of production just described

as something that is typical for all types of societies. In reality this is not

and doesn’t have to be the case. There are again at least two approaches: We

can positively describe how the expanded reproduction of capital (and the

reproduction of the economic base of society) takes place. This would mean to

assume the positing of its moments (e.g. labour as private labour of isolated

producers that is socialised by the market after production and the separation

of the main means of production and labour power) and to not further question

the moments. There would simply be capital, the production of commodities, the

selling of labour power etc., but it wouldn’t be argued why that’s historically

the case and how this capitalist situation could change or be overcome. Or we

can question from where these moments come from, whether they can be changed,

i.e. if they have developed historically and can be sublated. Or we analyse the

foundations of the existence of these conditions and hence also the possibility

of changing these conditions. Both approaches are scientific –

the first form corresponds to a positive science of the given (e.g. of the

political economy of capitalism), the second is critique (e.g. as the critique

of the political economy of capitalism). These forms represent typical examples

for Hegel’s logic of essence and logic of notion. In capitalism these

relationships are especially confusing: The driving power of production are not

the needs of the humans, but the “need of capital” to increase itself

(“Everything must be profitable!”, “Capital is shy like a roe deer – where it

can’t make profit, it won’t invest”). In capitalism goods are only produced

because they are a means to generate surplus value and profit – and

possibilities to avoid production and to increase capital nonetheless are

welcome (stock-market!). It seems like capital is the “subject of development”

itself, it turns itself loose and dominates and coins all human relationships.

In its different forms such as money it becomes a fetish which can’t simply be

shrug off as an illusion, but exists as “necessary appearance” as long as the

foundations which can only be recognised by the second form of thinking (critique,

logic of notion) are given. Something abstract, not concrete needs and concrete

actions determine social life! Such a “real abstraction” can induce one to use

as methodology an abstract level such as systems theories that remain purely

abstract. Such theories in fact map real relationships (the “necessary appearance”)

of this society, that’s why they are very convincing. Theories of

self-organisation even map the internal states of crisis and hence can be used

to avert and abandon political and political-economical intervention that is

necessary for realising social and ecological interests. An analysis whether

crises are only crises of renewal or which perspectives of sublation there are,

is only possible in a concrete-general manner by researching the concrete

qualitative moments of capitalist development (for the relationship of crisis

theory and self-organisation theory and a concrete analysis of Fordist and

post-Fordist capitalism as well as the societal crisis of Fordism see Fuchs

2002g). [i] For the relationship of logic of being,

essence and notion see Hegel 1830I/1986, p. 179 (§83), pp. 304ff (§159); see

also Schlemm 2002 [ii] “According to the notion of the duality of structure,

the structural properties of social systems are both medium and outcome of the

practices they recursively organise” (Giddens 1984: 25) and they both enable

and constrain actions (26). [iii] “To the member, society is his own community. […] To the servant,

society is an establishment, in which he finds his place. To the subject,

society is an imposed system, in which his place is determined. To the rebel. a

particular society is a tyranny; the alternative for which he fights is a new

and better society. To the exile, society is beyond him, but may change. To the

vagrant, society is a name for other people, who are in his way or who can be

used” (Williams 1961: 81). [iv] We don’t mean the temporal becoming, but

the systematic-logic one. [v] Translated from German [vi] Translated from German [vii] Concerning the critique of an absolutised

abstract view see Schlemm (1999: 25f), Schlemm (2001d: 17f). [viii] Whereas the “pure“ dialectical is the

transition of one moment into its opposed moment and the other way round, i.e.

it creates nothing new (Hegel 1830I/1986: 172 (§81)), the

“speculative-dialectical“ in Hegel’s philosophy means that this movement leads

to a higher unity (Hegel 1830I/1986: 176 (§82)). [ix] See Schlemm (1997/1998) This paper is published: Christian Fuchs, Annette Schlemm: The Self-Organization of Society. In: Zimmermann Rainer E.; Budanov, Vladimir G. (Eds)(2005): Towards Otherland. Languages of Science and Languages Beyond. INTAS Volume of Collected Essays 3. Kassel: kassel university press. p. 81-109. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||